Headstand (Sirshasana) does not increase the blood flow to the brain

HEADSTAND (SIRSHASANA) DOES NOT INCREASE THE BLOOD FLOW TO THE BRAIN

Minvaleev RS1, Bogdanov RR2, Bahner D3 , Levitov A4

1 St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia

2 Moscow Regional Research Clinical Institute. MF Vladimirsky, Moscow, Russia

3 The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Centre, Columbus, OH, USA

4 Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, USA

Abstract

Objectives: Most yoga practitioners believe that headstand (Sirshasana) results in increased cerebral perfusion. This however is not consistent with autoregulation of the cerebral blood flow. The intent of this study was to demonstrate the effect of Sirshasana on the blood flow to the brain via ultrasound examination of the Internal Carotid Artery (ICA).

Design, location and subjects: The ICA blood flow was measured with pulsed Doppler in 20 men and women aged 10 to 59 (median 43) while performing the headstand (sirshasana). 17 subjected were studied in 2018 in Spain at the altitude of 2000 m, while the other 3 females at the sea level.

Results: Although the diameter of the artery under examination during the headstand remained almost unchanged, the decrease in peak flow velocities in systole and diastole caused a significant decrease in arterial blood flow to the brain, followed by return to baseline values immediately after the anti-orthostatic postural effect, likely due to the expected consequences of the cerebral blood flow autoregulation of the cerebral blood supply as well as the intracranial pressure.

Conclusions: Contrary to popular belief, sirshasana does not increase blood flow to the brain through the ICA, but results in predictable reduction in cerebral blood delivery in compliance with known mechanisms of autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Moreover increasedICA blood blow while performing the headstand is likely to be a contraindication to this exercise

Keywords: Doppler ultrasound blood flow measurement, internal carotid artery, sirshasana

Background. According to the California Yoga Health Foundation about 20 million people practice yoga in theUS alone, and more than 250 million do so worldwide [Broad 2012, p. 27]. And it seems that the vast majority of them, as well as those who teach them, believe that «Regular practice of Sirshasana makes healthy pure blood flow through the brain cells… It ensures a proper blood supply to the pituitary and pineal glands in the brain» [Iyengar 1976, p. 90]. Yoga practitioners assume that Sirshasana should logically increase cerebral blood flow. This assumption, however, ignores cerebral blood flow autoregulation [Lassen 1959], that maintains same cerebral perfusion during acute severe changes in posture [Gelinas 2012].

It is important to consider that yoga headstand (Sirshasana) is different from the passive head down tilt just as getting up from a prone position cannot be equated to a head up tilt on the turntable. The differences are mostly due to muscular contraction of lower extremity and abdominal muscles (Hellebrandt 1943). Great muscular efforts are necessary to assume Sirshasana position, and may result in different cerebral profusion as opposed to passive tilt. Whether this muscular activity can affects cerebral blood flow during Sirshasana (antiorthostasis) was one of the objectives of this work.

Fig. 1. Ultrasound examination while performing sirshasana (headstand) at an altitude of 2000 m

Materials and methods

Subjects: We have examined twenty subjects ages 10 to 59 able to assume yoga head stand, either by themselves or with minimal help (Fig. 1). Subjects included 5 men and 15 women (see detailed description of the group in Table 1). 17 subjects were studied at the 2000 m. altitude while other 3 at sea level. Since data appeared concordant for both altitude and see level subjects and there was no expectation of altitude affecting cerebral blood flow data was combined. [Ainsle 2014] All the participants were able to assume headstand independently, however for safety reasons the feet were held as depicted in Figs 1 and 3.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the test group

|

NN |

Name |

Sex |

Age, yr |

Height, cm |

Weight, kg |

BMI |

Altitude, m |

Yoga experience, yr |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

MA |

m |

45 |

184 |

86 |

25.40 |

2000 |

1 |

|

2 |

BR |

m |

40 |

168 |

65 |

23.03 |

2000 |

5 |

|

3 |

MR |

m |

53 |

182 |

80 |

24.15 |

2000 |

32 |

|

4 |

KS |

m |

59 |

172 |

95 |

32.11 |

2000 |

1 |

|

5 |

PA |

m |

24 |

185 |

80 |

23.37 |

2000 |

2 |

|

6 |

EA |

f |

48 |

162 |

54 |

20.58 |

2000 |

4 |

|

7 |

VN |

f |

44 |

165 |

70 |

25.71 |

2000 |

10 |

|

8 |

KT |

f |

43 |

160 |

54 |

21.09 |

2000 |

2 |

|

9 |

TU |

f |

45 |

175 |

75 |

24.49 |

2000 |

1 |

|

10 |

IL |

f |

57 |

178 |

75 |

23.67 |

2000 |

3 |

|

11 |

MA |

f |

10 |

110 |

45 |

37.19 |

2000 |

0 |

|

12 |

AI |

f |

56 |

165 |

85 |

31.22 |

2000 |

15 |

|

13 |

PS |

f |

47 |

170 |

66 |

22.84 |

2000 |

1 |

|

14 |

AG |

f |

47 |

162 |

75 |

28.58 |

2000 |

1 |

|

15 |

GI |

f |

51 |

172 |

68 |

22.99 |

2000 |

1 |

|

16 |

KI |

f |

54 |

159 |

49 |

19.38 |

2000 |

13 |

|

17 |

BF |

f |

19 |

168 |

69 |

24.45 |

0 |

2 |

|

18 |

KI |

f |

22 |

165 |

64 |

23.51 |

0 |

3 |

|

19 |

TF |

f |

21 |

172 |

65 |

21.97 |

0 |

1 |

|

20 |

EP |

f |

23 |

162 |

53 |

20.20 |

0 |

5 |

|

Mean±SD |

40.4±14.9 |

166.8±15.5 |

68.7±13.3 |

24.8±4.4 |

|

|

||

The study was cleared by the Saint Petersburg State University Institutional Review Board. All the participants signed the informed consent form and willingly participated in the study without financial reimbursement.

Protocol: Two dimensional and Doppler ultrasound was performed using a Sonosite Edge II (Fujifilm Sonosite Ltd., Bedford UK) system equipped with the a L25 linear array probe able to image between 13-6 MHz. Data was collected between 8 and 12 am, in a quiet room with temperature 22-24 degrees C. All the subjects had time to familiarize themselves with the room and equipment prior to the study. Since most of the blood enters into the brain through the anterior system [Heistad 1983, Landwehr 2001], we have only studied blood flow through the common carotid artery. According to most authorities ICA, blood flow exceeds that of the vertebrbasillar artery, by no less than fivefold [Ho 2002, Oktar 2006].

Fig. 2. Ultrasound examination of the left internal carotid artery (LICA) in the supine position.

In supine position the diameter of ICA was measured in two dimensional 2-D mode, from intima to intima, and pulse wave Doppler was applied at an angle

This data allowed calculation of blood flow ml per minute. Similar parameters were obtained during the headstand (Fig. 3) and then again after reassuming supine position (Fig. 2).

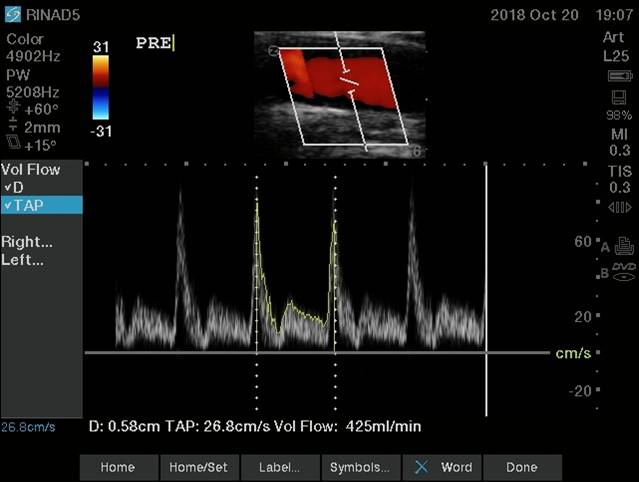

A typical ultrasound screen used for calculations is shown in Fig 4.

Fig. 3. Ultrasound examination of the left internal carotid artery in Sirshasana (headstand).

Fig. 4. A typical sample of ultrasound imaging of blood flow in the LICA of the subject MR. (53 years) in the headstand position. In the upper part of the picture there is a visualization of the blood flow in the artery under examination with a Doppler gate fixation in the middle of the vessel. Visualization of blood flow in the coordinates of speed and real time is presented in the middle of the figure. Numerical results are printed on the bottom line. The calculation of the volumetric blood flow was performed between the nearest systolic peaks (two vertical dashed lines).

Statistical processing of the results was carried out using Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test for related samples using the Origin 8.6 (c) program.

Results and discussion

Table 2 summarizes the results of evaluations of the studied characteristics, from those with ultrasonographic visualizations of the blood flow in the left ICA before, during and after Sirshasana. Separately Table 3 presents data for the participants who were unable to keep the position or were uncomfortable during it.

Table 2

The results of ultrasonographic assessments of the studied characteristics of blood flow in the LICA, presented in the form of a median and interquartile range. (p is the exact value of the probability of a 1-kind error calculated using the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test ; *** - the error probability is less than 0.001; ** - the error probability is less than 0.01; * - the error probability is less than 0.05; NS - no signifcant changes. Gray highlights significant changes.

|

Blood flow characteristics in LICA |

before |

during Sirshasana |

after |

|

Diameter Media to Media, cm |

0.59 |

0.6 |

0.58 |

|

Quintiles |

0.54 - 0.62 |

0.545 – 0.63 |

0.54 – 0.615 |

|

P values |

p = 0.05203(NS) |

|

|

|

|

p = 0.000488281*** |

||

|

p = 0.39597(NS) |

|||

|

Peak flow velocity in systole, cm/s |

94.6 |

59.3 |

84.9 |

|

Quintiles |

85.2 - 129.6 |

39.6 – 78.1 |

64.92 – 115.4 |

|

P values |

p = 0.0000152588*** |

|

|

|

|

p = 0.00232** |

||

|

p = 0.13166 (NS) |

|||

|

Peak flow velocity in diastole, cm/s |

24 |

18,2 |

24 |

|

Quintiles |

17.6 - 28.55 |

11.85 – 23.5 |

18.45 – 25.6 |

|

P values |

p = 0.00854** |

|

|

|

|

p = 0,00171** |

||

|

p = 0.63672 (NS) |

|||

|

Blood flow volume, ml/min |

471 |

347 |

464 |

|

Quintiles |

431 - 610 |

219.5 - 456 |

366.5 - 607 |

|

P values |

p = 0.000289917*** |

|

|

|

|

p = 0.01161* |

||

|

p = 0.35287 (NS) |

|||

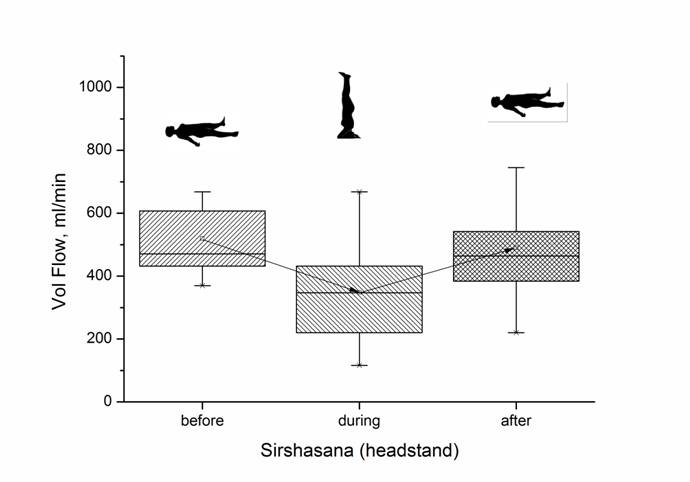

From table 2, it follows that, despite the fact that the diameter of the artery under examination remained practically unchanged during the headstand, the decrease in peak velocities in systole and diastole caused a significant decrease in arterial blood flow to the brain, followed by a return to baseline values immediately after the postural exposure that coincides with the expected consequences of cerebral autoregulation, which does not allow significant orthostatic changes in cerebral blood flow or pressure [Paulson 1990], during differentforms of physical activity[Jørgensen 1992, Querido 2007, Smith 2017], including the static ones [Rogers 1990]. In addition, cerebral autoregulation is preserved during orthostatic effects [Garrett 2017] and throughout the day [Guo WT 2018]. Our results confirm studies of alterations of cerebral blood flow during 5 minute passive head down tilt [Cooke 2003] as well as longer head down position [Montero 2018]. And despite the fact that the head-down angle in these studies did not exceed 10-30 degrees from the horizontal, changes in the blood flow to the brain coincided with our observations of the volumetric blood flow through the internal carotid artery during the active head-down 90 degree angle from the horizontal (Sirshasana). Therefore additional muscle tension did not affect the postural effects of anti-orthostasis on cerebral blood flow [Skytioti 2018]. For clarity, the last line of table 1 with our results of blood flow to the brain before, during and after Sirshasana reproduced in Fig. 5 like graphical interpretation in the form of box chart.

Fig. 5. Graphic interpretation of the average blood volume flowing through the left internal carotid artery before, during and after Sirshasana (headstand)

Separately, in Table 3 we presented sonographic findings in three subjects who during headstand subjectively experienced unpleasant feelings of fullness of the head, and increased intraocular pressure, which, by the way, is one of the known contraindications to perform Sirshasana [Baskaran 2006]. And indeed, their hemodynamic response to turning upside down was opposite to the main group, which follows from Table 3.

Table 3

Changes in the volume of blood flowing through the internal carotid artery in 3 people (1 man and 2 women’s) with a subjective difficulties with maintaining the headstand.

|

NN |

Name |

Sex |

The volume of blood flowing through the left carotid internal artery, ml/min |

||

|

before |

during Sirshasana |

after |

|||

|

1 |

IL |

f |

575 |

704 |

477 |

|

2 |

AI |

f |

512 |

809 |

619 |

|

3 |

KS |

m |

491 |

941 |

441 |

Cerebral blood flow through the ICAincreased significantly in these subjects either while standing on the head or immediately after performing the stand on the head of Sirshasana. It is the authors’ opinion that such increase in cerebral blood flow reflects failure of autoregulation and should be considered a contraindication to performing Sirshasana. Further studies however would be needed to support or disprove that notion

Limitations

We had not studied the effect of Sirshasana on systemic and intracardiac blood flow. This was addressed previously by Minvaleev 1996. Neither did we consider the muscular skeletal risk of the reverse positions previously studied [Broad 2012].

Conclusions

- The yogic posture of sirshasana (headstand) does not increase blood flow to the brain in healthy people.

- If in the antiorthostatic postures the blood flow to the brain through the internal carotid artery increases, then this person should not perform inverted poses.

Acknowledgment

The authors express deep gratitude to Irina Vladimirovna Arkhipova, General Director of the Faraon studio of historical films and the organizer and inspirer of international research expeditions as part of her author’s project “In Search of Lost Knowledge” (c) aimed at supporting russian science. The authors thanks also all members of the expedition "Pyrenees 2018".

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Broad WJ. The Science of Yoga. The Risks and the Rewards. NY, USA: Simon&Schuster, 2012:298.

- Iyengar BKS. The Illustrated Light on Yoga. New Delhi: Harpers Collins,2011:162

- Lassen NA. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol Rev 1959;39:183–238.

- Geinas JC, Marsden KR, Tzeng YC et al. Influence of posture on the regulation of cerebral perfusion. Aviat Space Environ Med 2012;83(8):751-757.

- Hellebrandt FA, Franseen EB. Physiological study of the vertical stance of man. Physiol Rev 1943;23(3): 220–255.

- Ainslie PN, Subudhi AW. Cerebral blood flow at high altitude. High Alt Med Biol 2014;15(2):133-140.

- Heistad DD, Kontos HA. Cerebral circulation. In: Shepherd JT, Abboud FM, Geiger SR, editors. Handbook of physiology: the cardiovascular system. Section 2. Bethesda: American Physiological Society, 1983:137-182

- Landwehr P, Schulte O, Voshage G. Ultrasound examination of carotid and vertebral arteries. Eur Radiol 2001;11(9):1521–1534.

- Ho SSY, Chan YL, Yeung DKW, Metreweli C. Blood Flow Volume Quantification of Cerebral Ischemia. American Journal of Roentgenology 2002;178(3):551–556.

- Oktar SO, Yücel C, Karaosmanoglu D, et al. Blood-flow volume quantification in internal carotid and vertebral arteries: comparison of 3 different ultrasound techniques with phase-contrast MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27(2):363-369.

- Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 1990;2:161–192.

- Jørgensen LG, Perko M, Hanel B, et al. Middle cerebral artery flow velocity and blood flow during exercise and muscle ischemia in humans. J Appl Physiol 1992;72:11231132,.

- Querido JS, Sheel AW. Regulation of cerebral blood flow during exercise. Sports Med 2007;37(9):765-82.

- Smith KJ, Ainslie PN. Regulation of cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise. Exp Physiol 2017;102(11):1356-1371.

- Rogers HB, Schroeder T, Secher NH, Mitchell JH. Cerebral blood flow during static exercise in man. J Appl Physiol 1990;68:2358 –2361.

- Garrett ZK, Pearson J, Subudhi AW. Postural effects on cerebral blood flow and autoregulation. Physiol Rep 2017;5(4):e13150.

- Guo WT, Ma H, Liu J, et al. Dynamic Cerebral Autoregulation Remains Stable During the Daytime (8 a.m. to 8p.m.) in Healthy Adults. Front Physiol 2018;9:1642.

- Cooke WH, Pellegrini GL, Kovalenko OA. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation is preserved during acute head-down tilt. J Appl Physiol 2003;95(4):1439-1445.

- Montero D, Rauber S. Brain Perfusion and Arterial Blood Flow Velocity During Prolonged Body Tilting. Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance 2016;87,8:682687.

- Skytioti M, Søvik S, Elstad M. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation is preserved during isometric handgrip and head-down tilt in healthy volunteers. Physiol Rep 2018;6(6):e13656.

- Baskaran M, Raman K, Ramani KK, et al. Intraocular pressure changes and ocular biometry during Sirsasana (headstand posture) in yoga practitioners. Ophthalmology 2006;113(8):1327-1332.

- Minvaleev RS, Kuznetsov AA, Nozdrachev AD, et al. Left Ventricle Filling in Sirshasana and Sarvangasana Yogic Postures. Human Physiology 1996; 25(6): 665-671. Translated from Fiziologiya Cheloveka 1996; 25(6): 27-34.

Файлы для скачивания: